These are some of the few details that have emerged about Brad Kelley, 55, a deeply private billionaire who made his fortune in the discount cigarette business. Mr. Kelley, whose hobbies include breeding rare, exotic animals, very rarely gives interviews. He doesn't tweet or use email.

He is also one of the largest private landowners in the country, spending by his own account hundreds of millions of dollars on about a million acres—or about 1,600 square miles. The state of Rhode Island, by comparison, has a land area of 1,215 square miles. According to the Land Report 100, which tracks land ownership, Mr. Kelley is the fourth-largest private landowner by acres in the U.S., just behind Liberty Media Chairman John Malone, media mogul Ted Turner and the Emmerson family, headed by timber magnate Archie Aldis Emmerson.

Mr. Kelley says it wasn't his goal to become one of the country's biggest landowners. "I grew up on a farm and that's about as good an explanation as there is," he says in an interview. "Land is something I know. It's something I have an affinity for. It becomes part of your DNA."

It has also become an increasingly popular investment in uncertain financial times. Some investors see land as a hedge against inflation, and low global interest rates have made land cheaper to buy. Higher world food prices and an anticipation of a recovery in the housing market have bankers pitching land as one of the few places to get real returns on an asset whose underlying value continues to rise. "It's a nonperishable commodity and it's as good a place as any to put my money," Mr. Kelley says. "It's better than derivatives."

Dennis Moon, head of the Specialty Asset Management team at U.S. Trust, the private-banking division of Bank of America (BAC), says land appeals to people as an investment they can easily understand. His clients have more than doubled their direct investments in irrigated farmland—land that produces crops like corn, soybean and wheat—over the past year to about $175 million, earning a net yield of some 4% a year. Others are more cautious, warning that the high rate of growth could mean the market is in a bubble, the risks being volatility in agricultural commodity prices, farmland values and farm production costs.

Ranches, which are Mr. Kelley's specialty, don't tend to yield much of an annual return. Instead, their value is in the underlying appreciation of the land: According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the national average value of U.S. ranchland rose 12% compared with five years earlier; in Texas, it is up 30% compared with five years ago. Investors make cash on ranches when they are subdivided and sold to developers or as "trophy ranches," where the wealthy can fish and hunt.

Texas oil baron T. Boone Pickens describes his strategy with ranches as "simple: Change the use of the land." He recently joined six other investors in a new ranch fund called Sporting Ranch Capital. The plan, says the fund's manager Jay Ellis, is to buy 12 to 15 premier ranches in Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Oregon and Idaho, fix them up and then resell them as "trophy sporting ranches." In August, the fund made its first purchase—a 760-acre ranch in Colorado with a 2.6-mile fishing stream and five lakes—for about $6 million in cash; the fund hopes to put it back on the market in 2014 for over $10 million.

Source: The Wall Street Journal

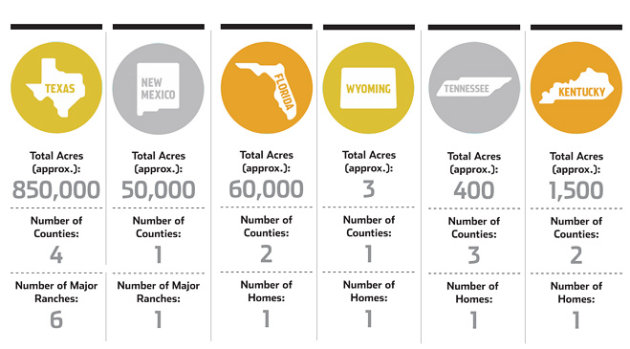

Source: The Wall Street JournalMr. Kelley's ranch strategy is different. He looks for good deals on cattle ranches in out-of-the-way places he thinks are undervalued, and holds on to them. He likes to buy adjoining parcels because it's more efficient to operate a ranch in large blocks and because it tends to be easier to buy property when it's right next door: He already knows what he's buying and what the seller is like. And he doesn't develop the land he buys: "We don't try to inject our way of doing things on other folks," he says. In this way, he has pieced together existing cattle ranches in remote parts of Texas, Florida and New Mexico.

Once he has bought the land, Mr. Kelley does what some ranchers call "resting." He keeps the cattle operations running, almost always leasing the land back to the previous owner, who already knows how to run the existing operation. Mr. Kelley says his operations break even. Several farmers and ranchers who work on land owned by Mr. Kelley didn't respond to requests for interviews.

The value of Mr. Kelley's land investments is difficult to calculate. "When he started buying ranches here, we all thought he was crazy," says Johnny Carpenter, an Alpine, Texas, real-estate agent who sold Mr. Kelley about half a dozen ranches in West Texas over a five-year period. Since then, the value of the land Mr. Kelley owns in those areas, known to be scenic with views of mountains, has doubled, Mr. Carpenter says. Chip Cole, a ranch broker in San Angelo, Texas, who was involved in the sale of about 15 ranches to Mr. Kelley, says prices doubled in 2005 and 2006. In 2008, sales volume dried up, making estimating current values more difficult, though Mr. Cole suspects values have softened. Few things make Mr. Kelley bristle more than being called a land speculator. He argues that he has sold about 15% of his total holdings over the past three decades; combined with the land he has bought, that's an aggregate turnover of less than half a percent, most of it for management reasons. "We take great pride in improving our property," he says, adding that he replaces and upgrades dozens of miles of fences annually and keeps water and wells running.

Read more Here

0 comments:

Post a Comment